Black doctors and nurses in Britain

During the nineteenth and twentieth centuries many people from countries in the Caribbean and Africa came to Britain to train and work as medical professionals. Some feature in this timeline, but there were many more (such as the Barbados-born physician Cecil Belfied Clarke, the Jamaican-born chiropractor James Acman Holland, or the Malawi-born doctor Hastings Kamuzu Banda), others were herbalists and therefore do not often appear in medical records, some studied in Britain and later returned their first homes, and many others are yet to be uncovered in the archives.

Mary Seacole travels to London

Mary Seacole, who had been employed as a nurse the previous year at Up-Camp Park, the headquarters of the British Army in Jamaica, travels to London. After her appeal to the War Office to be sent to the Crimea as an army nurse was refused, Mary raised funds herself to support her onward journey to Crimea to provide British soldiers fighting in the Crimean War (1853-1856) with food, accommodation and medical care.

A portrait photograph of Mary Seacole, BCA, SEACOLE/4.

Mary Seacole establishes the 'British Hotel' in Crimea

The ‘British Hotel’, near Balaclava, becomes a place of recovery for sick and wounded soldiers. Mary also visits the battlefield to nurse the wounded during this time. Sir William H Russell, War Correspondent for The Times newspaper, wrote of Mary in 1857, “I trust that England will not forget one who nursed her sick, who sought out her wounded to aid and succour them”.

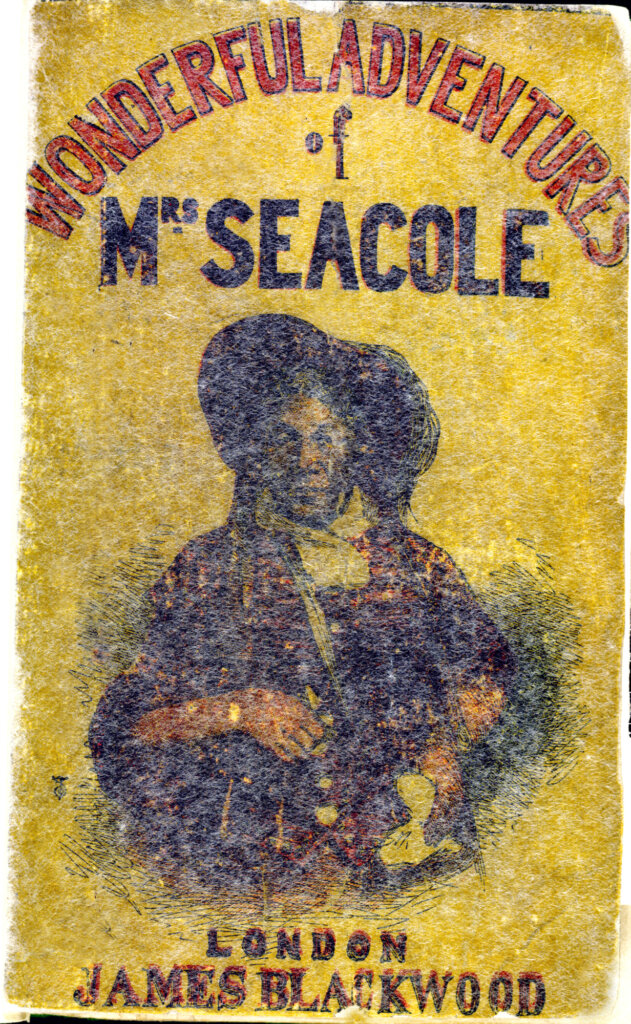

Wonderful Adventures of Mrs. Seacole

Mary Seacole’s autobiography, Wonderful Adventures of Mrs. Seacole in Many Lands, is published. It is thought to be the first autobiography of a Black woman to be published in Britain. At this point Mary is famous in both Jamaica and Britain. In the previous year, a four-night Thames-side gala held to raise funds for her work attracted over 80,000 attendees.

Portrait of Mary Seacole from her 1857 autobiography entitled Wonderful Adventures of Mrs. Seacole. From the British Library archive, 12601.h.20.

James Africanus Beale Horton

James, a West African medical doctor who studied first at King’s College London, graduates from the University of Edinburgh. After returning to West Africa to serve as a military doctor, he retires in 1880 having attained the rank of Lieutenant-Colonel.

James wrote West African Countries and People (1868), which contested theories of white racial superiority, and argued that African people were capable of creating modern, self-governing independent nations.

Annie Brewster

Annie Brewster (1858-1902), born in St. Vincent, begins her nursing career as a trainee at the London Hospital (now the Royal London Hospital) in East London. In the same year, Mary Seacole dies in London and is buried in St. Mary’s Catholic cemetery in North-west London.

Annie Brewster, via Wikimedia commons.

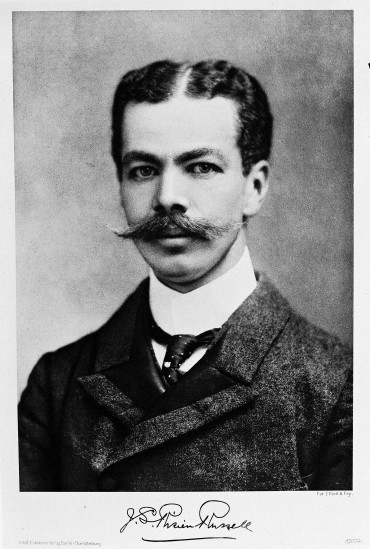

James Samuel Risien Russell

James Samuel Risien Russell (1863-1939), born in Guyana of mixed heritage, qualifies as a Doctor of Medicine from Edinburgh University. James soon begins working at hospitals in Nottingham and London. He would later become a professor at the University College Hospital, conducting research that focused on neurological conditions.

In 1902, James opened his own practice at his home at 44 Wimpole St, London. He also served as a captain in the Royal Army Medical Corps between 1908 and 1918.

Photograph of James Samuel Risien Russell circa 1900, via Wikimedia commons.

Nurse Brewster takes charge

Annie Brewster becomes nurse in charge of the Opthalmic Wards in the London Hospital. In her charge were many working-class East Londoners with poor eye health due to high levels of pollution.

She was promoted by the matron of the hospital Eva Luckes, who wrote in her notes that Brewster was popular among her colleagues, intelligent and a good ward manager. Eva Luckes herself was a pioneering matron who introduced more rigorous training for nurses and better working conditions.

Annie Brewster becomes widely known as ‘Nurse Ophthalmic’, specialising in treating elderly patients losing their eyesight.

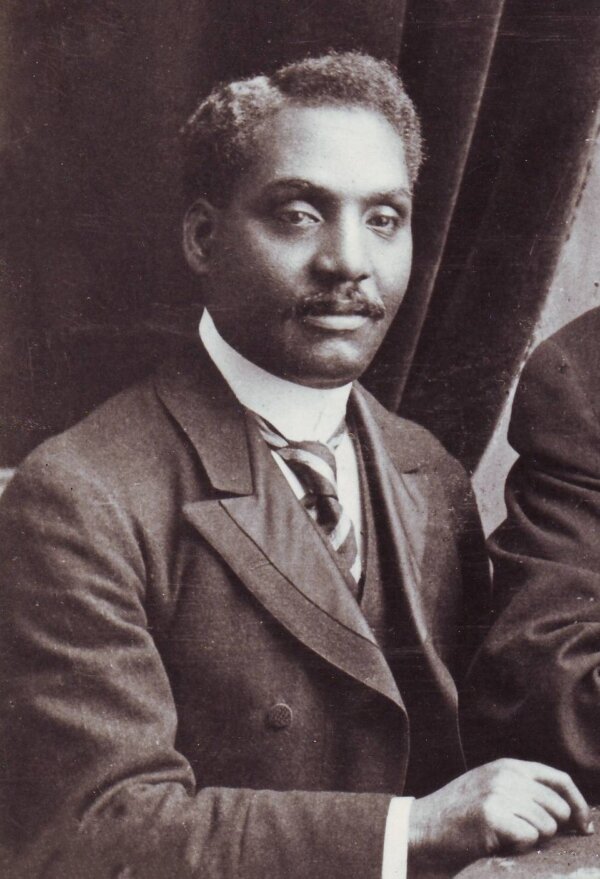

John Alcindor

John Alcindor (1873-1924), born in Trinidad, graduates from the University of Edinburgh, before moving to London to work at various hospitals and eventually establishing his own practice on Harrow Road in Paddington.

At the outbreak of the First World War in 1914, Alcindor tried to join the Royal Army Medical Corps, but is rejected in what is thought to be a racist decision. Instead, he joins the Red Cross as a volunteer and is awarded a medal for his care of soldiers.

Alcindor was also a member of United African League, attended the Pan-African Congress, and in 1921 became the second president of the African Progress Union, a predecessor to the League of Coloured Peoples, taking over from John Archer, a Pan-Africanist and Mayor of Battersea.

A photograph of John Alcindor, via Wikimedia commons.

Harold Moody

Harold Moody (1882-1947), born in Kingston, Jamaica, qualifies as a doctor at King’s College Hospital in London. After struggling to find employment due to racial prejudice, Harold opens his own medical practice first on King’s Road and later on Queens Road, Peckham.

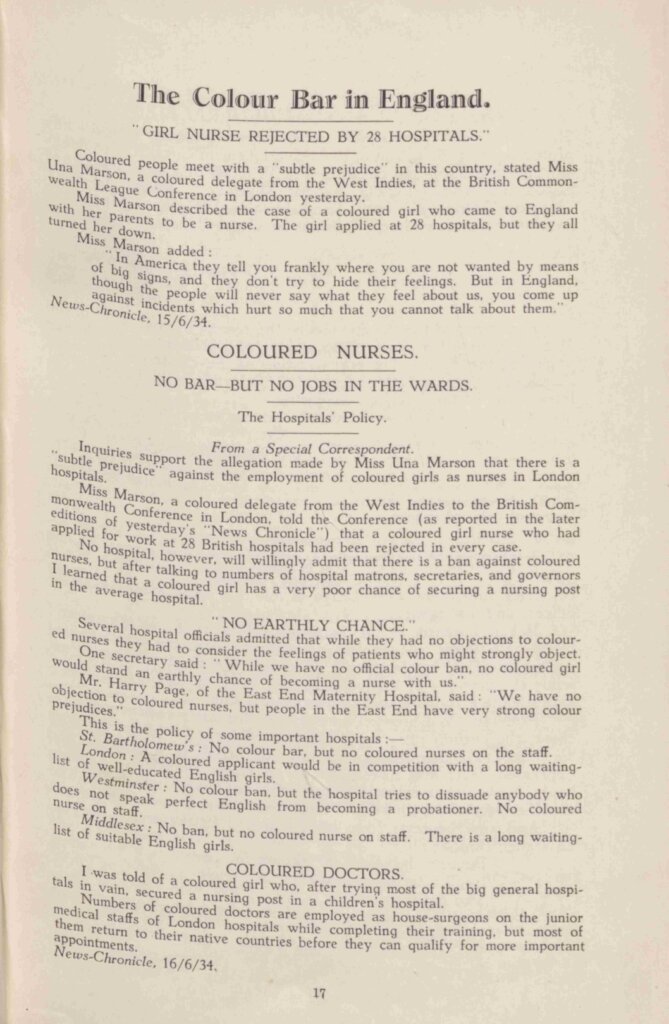

In 1931, Harold Moody founded the League of Coloured Peoples, aiming to promote and protect the social, educational, economic and political interests of Black peoples around the world. The first edition of the League’s journal, The Keys, speaks about the importance of training and supporting the careers of Black doctors and nurses in Britain who were experiencing racial discrimination: “The difficulties presenting themselves to men and women of colour who are anxious to undertake training in London as Medical men or nurses soon commanded our attention. One young lady applied to 25 Hospitals and was refused by everyone on the grounds of Colour.”

An article from The Keys journal entitled, ‘The Colour Bar in England,’ which reported on an investigation into the employment biases that qualified nurses were being subjected to. The author writes that: “Several hospital officials admitted that while they had no objections to coloured nurses they had to consider the feelings of patients who might strongly object. One secretary said: “While we have no official colour ban, no coloured girl would stand an earthly chance of becoming a nurse with us.” The Newspaper Archive, The Keys, July 1934.

Lulu Coote

Lulu Coote (1890-1964), who was born in Banana Point, Congo, to a Congolese mother and a Dutch father, qualifies in Manchester. Lulu had left Sierra Leone, where she was already working as a nurse. She worked in Manchester and Birmingham before retiring.

Olaore Green (1885-unknown) also travelled to Britain around this time. Born in Lagos, Nigeria, she moved to London in 1914 to study music theory at the London College of Music and midwifery at the Clapham School of Midwifery. She then trained as a pharmacist at Westminster College, later becoming a medication dispenser at Soho Eye and Ear Hospital. Her time in London was brief; she left for Lagos in 1917 where she worked as a midwife at the hospital of Dr. Richard Akinwande Savage (father of Agnes Yewande Savage), until Green opened her own medical practice in the 1920s.

James Jackson Brown

James Jackson Brown (1882-1953), born in Jamaica, qualifies to practice medicine after working at The London Hospital. He starts his own medical practice at different Hackney addresses before settling at 63 Lauriston Road. Like his friend, John Alcindor, James was also turned away by the Royal Army Medical Corps during the First World War. His passing in 1953 was headline news in the Hackney Gazette, which described him as a popular local doctor.

Agnes Yewande Savage graduates from her medicine degree at University of Edinburgh

Agnes Yewande Savage (1906-1964) was born in Edinburgh to a Sierra-Leonian-Nigerian doctor and journalist, Richard Akinwande Savage (who also trained at the University of Edinburgh), and a Scottish mother, Maggie Bowie. She becomes a doctor in 1929, just two years after her brother Richard Gabriel Akinwande Savage, who qualified at the same university. Richard would become a military officer and doctor during the Second World War, whereas Agnes moved to Ghana to work as a medical officer and teacher at various hospitals and training centres throughout Accra.

A photograph of Agnes Yewande Savage from a 1929 publication, via Wikicommons.

Midwife Princess Adenrele Ademola travels to London with father

Princess Omo Oba Adenrele Ademola (1916-unknown), daughter of Ladapo Ademola, the Alake of Abeokuta, Nigeria, travels to London as a midwife. She trains at St. Guy’s Hospital, becoming a registered nurse in 1941. She receives further training in midwifery at Queen Charlotte’s Maternity Hospital and subsequently works at the New End Hospital. Not much is known about her career after the 1940s.

Princess Adenrele Ademola is one of many nurses from Britain’s African colonies who trained and worked in Britain. Some chose to remain in Britain, while others returned to the countries of birth or went on to other countries to continue their medical careers.

Princess Adenrele Ademola circa 1944, via Wikicommons.

Albert Kagwa

Albert Kagwa (1915-1963), son of Ugandan political leader, Sir Apollo Kagwa, qualifies to practice medicine after studying at St. Dunstan’s College in Catford and later at the London Hospital. He worked in several hospitals, including as house physician at the Isle of Wight County Hospital in the mid 1940s, and served as a lieutenant stationed in Burma during the Second World War, marching alongside East African troops in the Victory Parade. He returned to Uganda in 1953, working as a doctor and expert on nutrition.

Building the National Health Service

The NHS was established in 1948. Many healthcare workers, particularly nurses and midwives, were recruited from 16 British colonies to help address post-war labour shortages. Working in the NHS, racialised staff would go on to experience exploitation and discrimination from both colleagues and patients. Less desirable roles and tasks would be more often assigned to Black staff. Patients would sometimes refuse treatment from migrant healthcare workers or racially abuse them, whilst in some cases colleagues would create a hostile environment. Nonetheless, Black healthcare workers persevered and have been integral to the running of the NHS ever since.

The British Nationality Act is passed

The British Nationality Act 1948 is passed in the same year as the establishment of the NHS. This Act, introduced to address the post-Second World War labour shortage, allowed those living across the Commonwealth to settle in Britain and become British nationals, or Citizens of the United Kingdom and Colonies (CUKC).

Joan Andall, a State Enrolled Nurse originally from Grenada, who worked at Hammersmith Hospital among others. Photograph from the CAW family collection.

Kofoworola Abeni Pratt qualifies as a State Registered Nurse

The Nigerian-born Kofoworola Abeni Pratt arrives in Britain in 1946 to study nursing at St. Thomas’s Hospital in 1946, qualifying in 1949. She is thought to be among the first Black nurses to work in the NHS. She went on to receive qualifications in midwifery and tropical medicine and in 1955 she would return to Nigeria. It is here that she held many leadership positions in Nigeria’s healthcare services and training. For example, in 1965 she founded a School of Nursing at the University of Ibadan and in 1973 she became the Commissioner of Health for the country.

Medical secretary and campaigner Connie Mark (then Goodridge) moves to West London

Connie Mark (1923-2007), who had trained and worked as a medical secretary for the Auxiliary Territorial Service and the Women’s Royal Army Corps in Jamaica during World War II, moves to West London with her young family. Once settled, she finds work as a medical secretary at Charing Cross Hospital. In the UK she becomes a community activist, working to shine a light on the war efforts of Caribbean service personnel and the legacy of Mary Seacole.

Connie Mark pictured with colleagues at Charing Cross Hospital. BCA, BCA/5/1/109.

Dawn Hill leaves Jamaica for Britain to take part in the pre-nursing Cadet Scheme in Leicester

Hill would qualify as a State Registered Nurse in 1960 and go on to work as a theatre nurse in numerous hospitals in London in throughout the 60s, eventually rising to the ranks of Senior Theatre Sister in the Neurosurgery department at the Brook General Hospital in Greenwich, London. Along the way she would experience racial discrimination in the workplace when she was placed in a lower grade role, not in line with her skills. In 1971, she would begin her studies at LSE in Social Administration and Policy, leading her to create more equitable policies in workplaces across Hackney hospitals.

Dawn Hill would also go on to serve as a board member for the Mary Seacole Memorial Statue Appeal from 2011, and as the Chair of Black Cultural Archives in 2012, retiring in 2023.

Photograph of Dawn Hill in her nurse’s uniform. BCA, PHOTOS/153.

Enoch Powell becomes Minister of Health

Enoch Powell begins a three-year term as Minister of Health in Harold Macmillan’s government, during which he extends further invitations to people from the Caribbean to train as nurses in Britain. Eight years later, on 20th April 1968, Powell would deliver his ‘Rivers of Blood’ speech in Birmingham which criticised the level of immigration from the Commonwealth to Britain and attacked the Race Relations Bill that was making its way through Parliament.

The Race Relations Act 1968 expanded the provisions of the 1965 Race Relations Act, which had banned racial discrimination in public places and made promoting racial hatred a crime. The 1968 Act was intended to end discrimination in housing and employment. It aimed to ensure that the second-generation immigrants “who have been born here” and were “going through our schools” would get “the jobs for which they are qualified and the houses they can afford”.

Commonwealth Immigrants Act

The Commonwealth Immigrants Act is passed in 1962, amid increasing racism in the UK, which restricts immigration from Commonwealth countries. However, the act made allowances for highly skilled professionals such as qualified doctors and nurses. Nonetheless, the Act was opposed by the Labour Party, who labelled it discriminatory, and by activists like Claudia Jones, who recognised it as a severe manifestation of the colour bar.

Daphne Adriana Steele becomes the first Black matron in Britain

Born in Guyana to a father who was a pharmacist, Steele began her nursing training in Guyana’s capital, Georgetown. She finished her training at St. James’ Hospital in Balham, upon moving to Britain in 1951. After a short time in nursing in the US in the middle of the 1950s, she returned to the UK, working as a nurse in various hospitals across the country. She settled in Ilkley where she becomes the first Black matron in Britain at St Winifred’s.

This achievement was significant – 16 years after the establishment of the NHS – in the context of the continued encounters with racism as healthcare workers. Though Black healthcare workers did not experience the same colour bar of the early 20th century that was reported in The Keys, they were still exposed to discriminatory colleagues, patients, and workplace policies.

The Briggs Report is released

The Briggs Report from the Committee on Nursing examines the roles of midwives and nurses in hospitals and community care. Over a decade later the recommendations of this report would lead to the phasing out of the State Enrolled Nurse (SEN) job, a position often held by African and Caribbean staff. This position required less training and was considered to be more practical, was less respected and worse paid compared to its counterpart: State Registered Nurse (SRN).

Campaigning against Medical Racism

Despite the Race Relations Acts of 1965, 1968 and 1976 - created to target discrimination against people because of their race, ethnicity or skin colour - Black healthcare workers and patients continued to experience racism in the workplace and whilst accessing healthcare services. Black healthcare workers, patients and community activists mobilised to secure better working conditions, treatment and recognition.

The Brixton Black Women's Group (BBWG) is founded

The BBWG is a socialist feminist organisation for Black and Asian women. A key focus in its organising and its later publication Speak Out (1979-1983) is health and health care. In their book Heart of the Race, Beverley Bryan, Stella Dadzie, and Suzanne Scafe write about the intersecting experiences they, and other Black, working-class women, face when accessing healthcare in post-war Britain:

“With sick children, elderly relatives, and the general needs of the entire family failing squarely on our shoulders – quite apart from our many specific needs as women – it is little wonder that we frequent the hospitals, clinics and doctors’ surgeries in such disproportionate numbers. Because we are working class women, we have no access to the growing number of private or natural alternatives, so favoured by those with the financial resources to go elsewhere. But above all, because we are Black women, whether we seek treatment within or outside the NHS, we invariably find ourselves dealing with a profession which is fundamentally patriarchal and racist” (p. 90).

The 'Ban the Jab' campaign launches

The Ban the Jab campaign launches which seeks to stop the prescription of the contraceptive injection Depo Provera which was being disproportionately administered to Black and working class people in the UK. The authors of Heart of the Race speak about the need for the campaign; they write that “Cancer of the breast and cervix, long-term infertility, irregular or absent menstrual bleeding and massive weight gain have been evident in many women who have received the drug. And some of these side-effects were evident over two decades ago, when its multi-national manufacturers, Upjohn, were testing the drug on monkeys and beagle dogs. However, this was not enough to prevent DP being distributed widely among Black women in Britain, the US and particularly Third World countries.” (p. 106).

A logo for the ‘Ban the Jab’ campaign. BCA, DADZIE/1/6.

The campaign importantly aims to educate women about the contraceptive as they found that women were regularly prescribed Depo Provera without their full knowledge. In a Speak Out article, the Brixton Black Women’s Group outline why they support the campaign: “…it is because we recognise the dangerous and racist implications of the use of all contraceptive injections that we joined with others concerned about womens’ welfare in forming a national campaign against Depo Provera. The campaign has been in operation for nine months. During that time we have tried to spread information gained about the drug’s use through leaflets in local groups, articles in the newspapers, talks at conferences and two T.V. programmes. We are seeking to inform women so they can take up the issues themselves, making their own demands on doctors and the Health Service.”

An article from the third issue of Speak Out, entitled ‘ABORTION BILL – Fight the new proposals – WHOSE CHOICE?”. BCA, DADZIE/1/8/3.

The first Sickle Cell and Thalassaemia counselling centre opens in the UK

Working as a nurse and health visitor Elizabeth Anionwu notices how families impacted by Sickle Cell are underserved and how NHS staff are insufficiently trained to make a Sickle Cell diagnosis. She works with Dr Milica ‘Misha’ Brozovic to establish the Sickle Cell and Thalassaemia Counselling Centre in Brent, the first of its kind in the UK. It would lead to increased self-referrals and screenings in Brent and throughout London.

In the same year, Anionwu establishes the Sickle Cell Society to tackle the lack of information and support available to Black communities. She would travel to Jamaica and the US to get materials like posters and films to support the society’s work, as they were more readily available. This is because at the time in Jamaica there was a research council dedicated to Sickle Cell and in the US the Black Panthers had created a wealth of resources as part of their community health programmes. In the leaflet pictured below, the society’s aims are listed as: to support families and individuals affected by sickle cell disease; to increase general awareness of sickle cell disease through film shows and publication leaflets; to campaign for better services for people with sickle cell disease and for more research into treatment and prevention.

A leaflet produced by the Sickle Society with information about Sickle Cell disorder and the Sickle Cell trait. BCA, RC/RF/10/05.

Margaret Thatcher announces cuts to the NHS budget

Margaret Thatcher wins the election and becomes Prime Minister. Almost immediately she announces cuts to the NHS budget, which would impact Black working class patients and workers disproportionately. As an article in Speak Out explained, “The Health Minister has told London Area Health Authorities that they must cut £38m off their budget. In Merton, Sutton and Wandsworth area this means the closure of four hospitals, plus specialist units and wards, and of course, a cut to all staffing sectors, (expect, not surprisingly, managerial and administrative). This would include nurses, domestics, and porters to name a few. Since many Black women work in all sectors of the Health Service the effect on our employment chances will be devastating. It also means that more and more student nurses will be herded into being State Enrolled nurses (SEN) as opposed to being State Registered Nurses (SRN).”

An article in BWG’s Speak Out publication entitled, ‘Cuts Will Kill’. BCA, DADZIE/1/8/3.

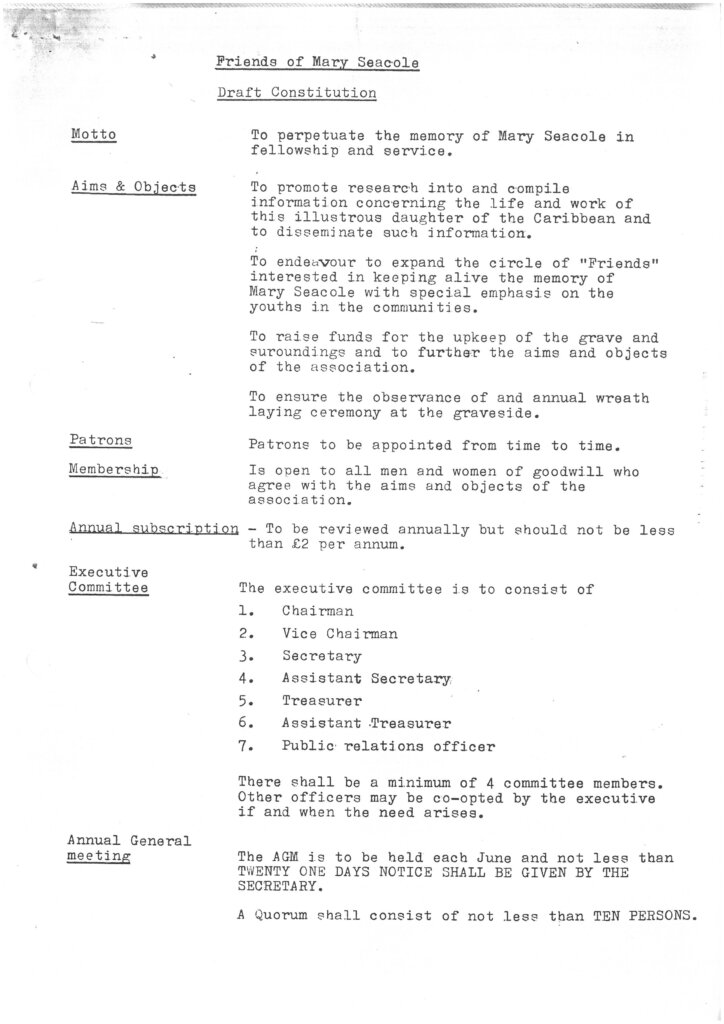

The Friends of Mary Seacole is founded

A century after the death of Mary Seacole, the Friends of Mary Seacole, now Mary Seacole Memorial Association, was founded by medical secretary and activist Connie Mark, midwife Shirley Graham-Paul and Vie Lawrence. According to the group’s draft constitution it was established “to perpetuate the memory of Mary Seacole in fellowship and service”. We can see in the draft constitution below, their aim to maintain Seacole’s grave at St. Mary’s Catholic Cemetery in order to show respect for her accomplishments as a Black nurse and to remember her each year in a wreath laying ceremony.

This Horrible Histories clip makes evident the role racism plays in the differing legacies of the lives and careers of Mary Seacole and Florence Nightingale.

The draft constitution for the Friends of Mary Seacole, which states its motto, aims, committee members and information about membership. BCA, SEACOLE/9.

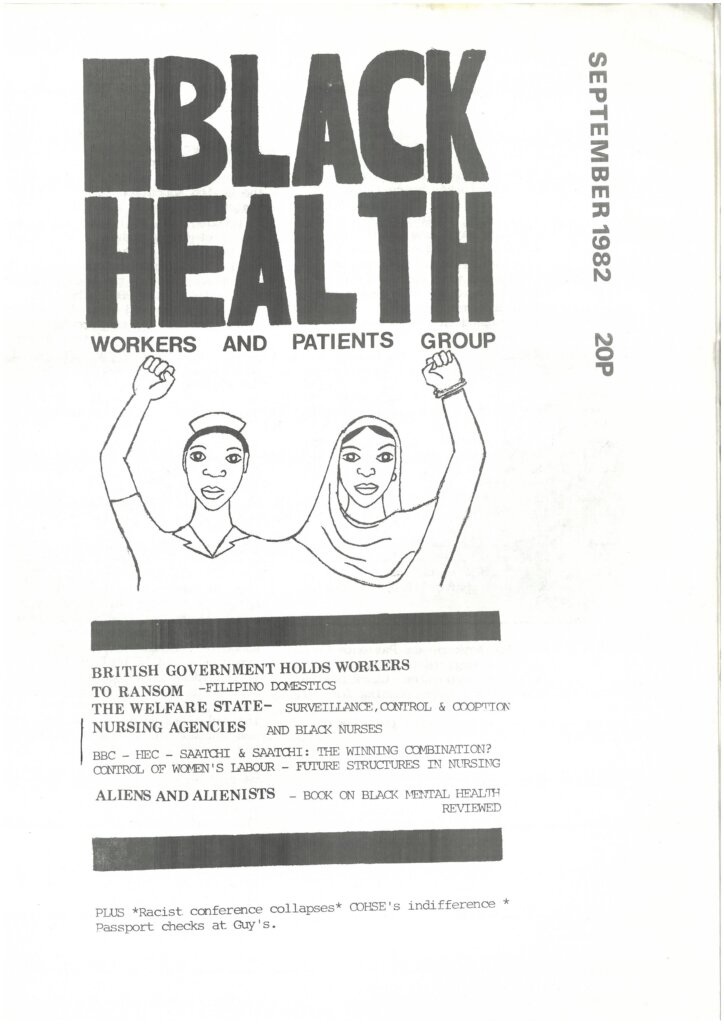

The Black Health Workers and Patients group is established

Brent Community Health Council releases a report entitled ‘Black People and the Health Service’. The report finds that, “racism often determines the way black patients and workers are treated, that it dictates official policies on health, and that it is institutionalised in the Health Service”. Out of this report develops the Brent Black Health Workers and Patient group, which soon becomes the Black Health Workers and Patients group. Their first bulletin is published in November 1981 and is full of articles primarily on experiences of Black nurses and patients. One article, ‘Conforming to White Image’, described nurses experiencing hair discrimination when wearing braids or other natural hair styles (which met General Nursing Council regulations). This led to nurses experiencing humiliation from colleagues or even being deprived of work, in the case of agency nurses.

Another nurse wrote about her situation working as a Black woman at St. Ann’s Hospital. She compares her experience to conditions of slavery, describing a racialised hierarchy where Black nurses are given the hardest tasks, work the longest hours and receive racist verbal abuse from patients.

The front page of the second issue of the bulletin produced by Black Health Workers and Patients group, published in September 1982. BCA, DADZIE/3/2/2.

Another Mary Seacole memorial service takes place at her graveside at St. Mary's Catholic Cemetery

At this year’s annual memorial service for Mary Seacole, a speech is delivered at her graveside by Catholic leader Leela Ramdeen, who remarks on the suppression of Seacole’s legacy. Ramdeen says, “As we stand at this grave, let us draw the veil of secrecy which has shrouded the truth about this Black woman called Mary Seacole…The history of Black people has either been suppressed or destroyed by White historians.”

Leela Ramdeen and others after her speech at Mary Seacole’s graveside, Connie Mark is also pictured. BCA, BCA/6/3/20.

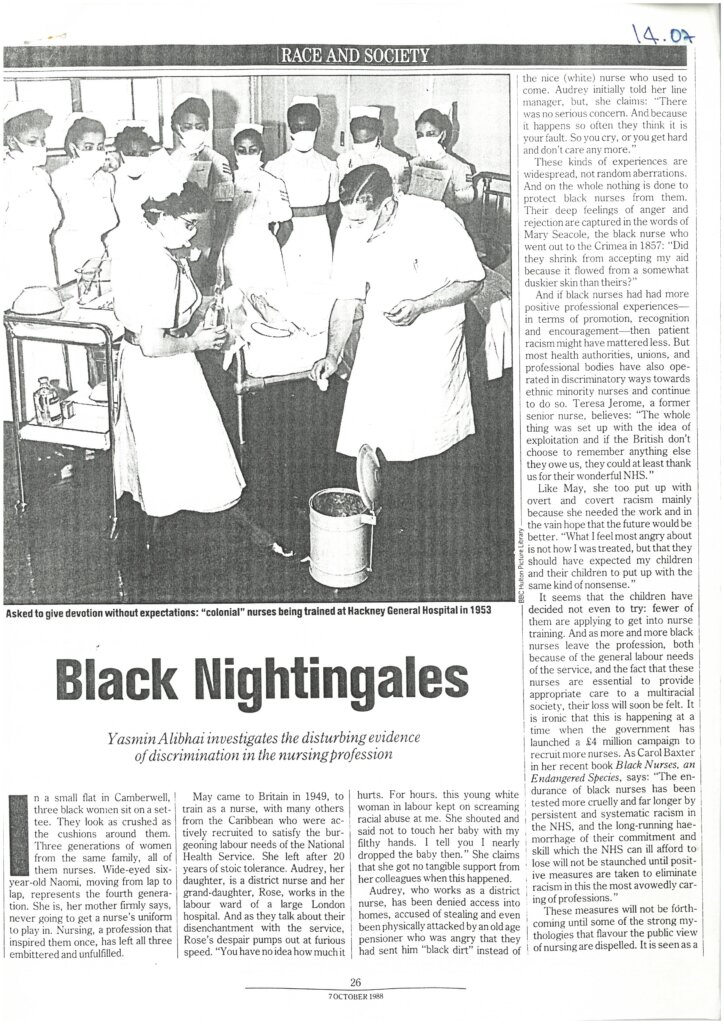

In the article below entitled, ‘Black Nightingales’, on the racism Black NHS staff experienced, the author writes, “These kinds of experiences are widespread, not random aberrations. And on the whole nothing is done to protect black nurses from them. Their deep feelings of anger and rejection are captured in the words of Mary Seacole, the black nurse who went out to the Crimea in 1857: “Did they shrink from accepting my aid because it flowed from a somewhat duskier skin than theirs?”

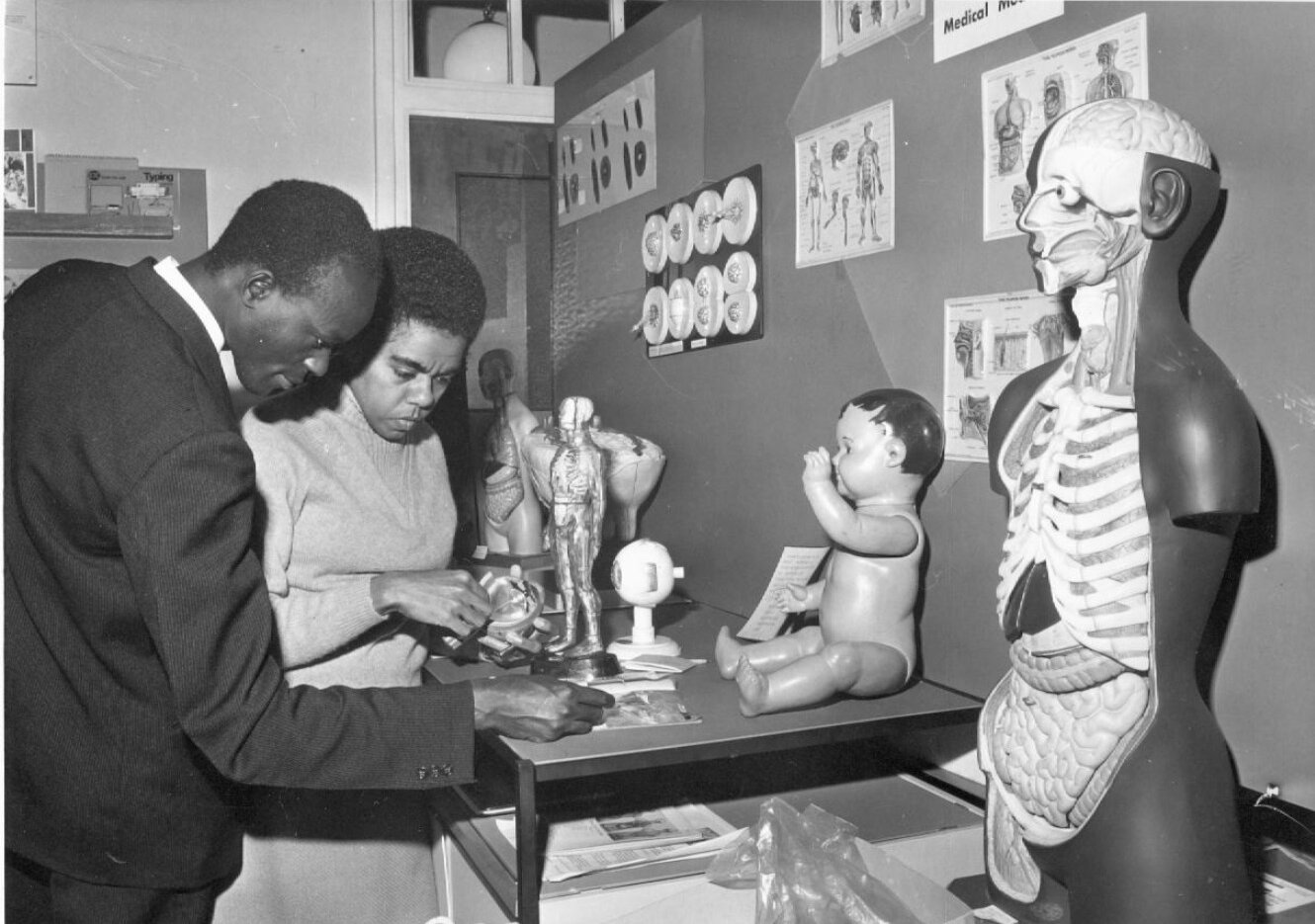

An article from the New Statesman and Society entitled ‘Black Nightingales’ with an image a group of Black nurses in a training session at Hackney General Hospital in 1953. BCA, RC/RF/14/07.

Blackliners is established to support Black people with HIV and AIDS

Blackliners begins as a telephone helpline for Black people with HIV and AIDS seeking support, set up by Arnold Gordon from his home in Balham, London. It quickly grew exponentially and moved to an office in Brixton. Dawn Hill also became involved in the organisation. Blackliners provided many services for those who were experiencing the intersecting prejudices of homophobia and racism; for example, the organisation helped secure housing for those with HIV/AIDS who had been made homeless.

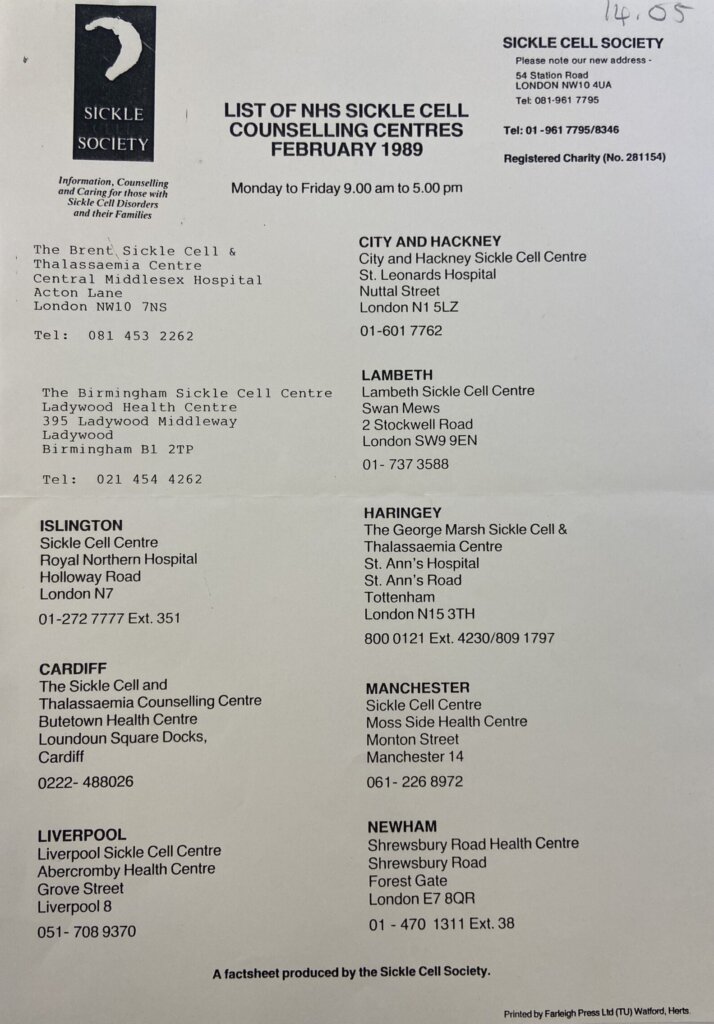

Sickle Cell counselling centres increase in numbers

Here we can see a list of NHS Sickle Cell counselling centres from 1989. 10 years after the establishment of the first Sickle Cell Counselling centre, this list demonstrates that the health service is trying to respond to the demands from organisations like the Sickle Cell Society for better healthcare for Sickle Cell patients.

A list of Sickle Cell counselling centres in the UK in 1989. BCA, RC/RF/10/05.

Mary Seacole exhibition opens

An exhibition on the life of Mary Seacole opens at the Florence Nightingale Museum. Headlines that reported on the exhibition include, ‘Heroism acknowledged at last’, ‘Forgotten heroine’, ‘Mary Seacole, Saviour of the White Sick and Wounded Enters History’, and ‘Overdue Celebration Held for Life of Neglected Black Leader’.

A headline from an issue of the Nursing Times published on May 27th 1992, BCA, BCA/6/7.

Melba Wilson becomes the national and London director of Delivering Race Equality in Mental Health Programme

The mental health and race researcher and campaigner and member of the Brixton Black Women’s Group, Melba Wilson becomes the national and London director of the programme for Delivering Race Equality in Mental Health. She had previously served for 5 years as the policy director for Mind. In response to the death of the Jamaican-born David ‘Rocky’ Bennett, who died whilst being physically restrained at a mental health unit in Norwich where he was receiving treatment for schizophrenia in 1998, an inquiry was published in 2003 that found that institutional racism was plaguing mental health services. The programme for Delivering Race Equality in Mental Health is launched in response to improve access and experiences of Black Minority Ethnic people struggling with their mental health.

Front page of the Mind publication A-Z of Race Issues in Mental Health by Wilson. In the publication Wilson writes about experiences of discrimination being a significant cause of mental health issues among Black Britons, the poor treatment of Black mental health service users and the work of Black community organisations that are filling in the gaps left by the NHS. BCA, WILSON/13.

Nubian Jak unveils a blue plaque for John Alcindor at the site of his former medical practice in Paddington

Nubian Jak Community Trust, established in 2006, works to memorialise the lives of significant Black and ethnic minority figures living in Britain, through plaques and statues. John Alcindor’s plaque is found at his former medical practice at 209 Harrow Road in Paddington, London. Nubian Jak have also erected blue plaques for Connie Mark, Cecil Belfield-Clarke, and Harold Moody.

John Alcindor’s blue plaque in Paddington, London, via Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain.

A statue of Mary Seacole is erected

A statue of Mary Seacole is erected in the gardens of St Thomas’ Hospital in Lambeth, London, after the Mary Seacole Memorial Statue Appeal campaigned and raised funds over 12 years. The campaign for the statue faced opposition from the Nightingale Society, who took issue with St Thomas’ Hospital memorialising both Florence Nightingale and Mary Seacole (the Florence Nightingale Museum is located at St Thomas’ Hospital because of Nightingale’s work there). The society states that “while it supports the inclusion of Seacole in the school curriculum, it does not support the pairing of Nightingale and Seacole, who made very different contributions”.

The statue of Mary Seacole erected outside St Thomas’ Hospital in 2016, via Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain.

The first Black Maternal Health Awareness Week is established

Five X More, an organisation founded in 2019 to support Black women and birthing people and healthcare workers to ensure better outcomes during pregnancy and birth, establishes Black Maternal Health Awareness Week. Since then it has been observed annually to raise awareness of their campaign and highlight the impact of medical racism on maternal care.

No One's Listening inquiry is published

The All-Party Parliamentary Group on Sickle Cell and Thalassaemia (SCTAPPG), with the support of the Sickle Cell Society, conducts an inquiry called ‘No One’s Listening’ on avoidable deaths and inadequate care for sickle cell patients. The inquiry finds that sickle cell patients “too often receive sub-standard care” particularly in A&E departments and in Community care. It also finds “low levels of awareness and insufficient training in sickle cell” and evidence of the role of racism in treatment and negative, dehumanising experiences of sickle cell patients.

The Mary Seacole Trust and the Florence Nightingale Foundation take over the operation of the Mary Seacole Awards

The Mary Seacole Awards, funded by Health Education England with the support of the Royal College of Midwives, the Royal College of Nursing, UNISON and Unite, is delivered by a partnership between the Mary Seacole Trust and the Florence Nightingale Foundation for the first time. The awards fund Black and minority ethnic people who are working, researching and innovating in ways that produce better health outcomes for Black and minority ethnic health service users.

Some of the previous awardees talk about their motivations behind their work and the legacy of Mary Seacole.

Annie Brewster's grave is restored

With the support of the Royal British Nurses’ Association, a restoration of Brewster’s grave is revealed at a ceremony. Three years prior, historian Stephen Bourne located the grave in the City of London Cemetery, finding it in a poor state. The ceremony is attended by many nurses, including Cenio E Lewis, the high commissioner for St. Vincent and the Grenadine, who trained as a mental health nurse upon moving the the UK in 1967.

In the same year, the Royal College of Nursing conducts an employment survey and finds that white nurses are twice as likely to get a promotion when compared to ethnic minority nurses.

Mary Seacole statue is vandalised

In August, in what is thought to be a racially-motivated incident, Mary Seacole’s statue outside St Thomas’ Hospital is vandalised.

Elizabeth Anionwu is honoured with a plaque at the Brixton Blood Donor centre

The centre was established in the previous year to encourage local Black community members to donate blood and support the treatment of Sickle Cell through blood transfusion. In the first few months of opening, 3,773 people donated blood, 1,000 of those being new donors. 7% of donors at the Brixton Blood Donor centre had the Ro blood sub-type that is so vital to Sickle Cell treatment, which compares to an average of 2% of donors donor centres nationally. Over half of Black donors have the Ro blood sub-type.

Lord Victor Adebowale, chair of the NHS Confederation, states that Black healthcare users do not get the service they deserve

Lord Victor Adebowale, who played a role in setting up the NHS Race and Health Observatory in 2021, lost his mother to lung cancer earlier in the year. She died undiagnosed and Adebowale states this is because “she got a black service, not an NHS service”. Cancers like ovarian and colon are more likely to be diagnosed at a late-stage in minoritised patients compared to white patients. He explains that the NHS is plagued by racial inequalities; he states, “It’s the inverse care law. The people most in need of health and care are the least likely to get it – if you are black, if you are poor, if you are elderly and poor, there are inequalities in the system and people like my mum suffer.”

Adebowale’s mother, Grace, worked as a nurse for the NHS after moving to the UK from Nigeria in the 1950s. Of his mother, Adebowale says, “She believed in the health service. It’s people like her who help build the NHS, but, when she needed it, it wasn’t there as it should have been.”

Lord Victor Adebowale, via Wikimedia commons.

Credits

Black Cultural Archives Timelines are brought to you through a collaboration between Black Cultural Archives and Royal Holloway, University of London. Our five-year partnership, launched in 2023, aims to make the teaching and learning of inclusive, shared histories available for everyone. Many of the documents and artifacts presented are from BCA’s unique archival collections, digitised to support access to a broader audience.

Project Team:

Dr. Ayshah Johnston, Learning and Engagement Manager, Black Cultural Archives.

Dr. Matthew Smith, Senior Lecturer in Public Humanities, Royal Holloway, University of London.

Carmen Andall Woodroofe, PhD candidate, Department of Music, Royal Holloway, University of London.

Where next?

Collections

Search our Subject Guides for information on Enslavement and Reparations. Search the Catalogue for BCA’s archival materials which are available to view in our reading room.

Explore BCA collections

Workshops

Our range of school, higher education and adult workshops includes Black Abolitionists in Georgian London. Bespoke workshops may also be considered.

Book a Workshop

Resources

Learn more about the Young Historians Project and their work on African women in the Health Service, which includes oral history interviews and photos.

Young Historians Project